Microsoft's development direction of Internet Explorer 9 is unambiguous: implementing HTML5 Web standards is the name of the game, with the intent of letting developers use the "same markup" to work everywhere. As IE General Manager Dean Hachamovitch said at MIX10 this week, "We love HTML5 so much we actually want it to work."

Redmond is targeting real-world applications based on real-world data. For example, every single JavaScript and DOM API used by the top 7,000 websites was recorded. IE9 will deliver support for every API used by those sites.

That obviously gives rise to a chicken-and-egg situation—what about the APIs that developers can't currently use because of a lack of widespread support, but would like to? Beyond the top 7,000 data, Microsoft has a number of HTML5 usage scenarios that it's targeting. The company has not said much on what those scenarios are, but given the demonstrations of HTML5 video and SVG animation, it seems that these are clearly viewed as core technology for a future HTML5-powered Web.

This dedication to HTML5 does not, however, mean that Microsoft is going to devote considerable effort to, for example, the SunSpider benchmarks or the Acid3 test. As the browser develops, the scores in those tests will likely improve (it currently gets 55/100, a marked improvement on IE8's 20/100), but they're not the number one priority. Acid3 is a scattergun test. It's not systematic—you can implement a high proportion of a particular specification and not pass the test, or a much lower proportion but still pass—and though many of the features it tests are useful, that's probably not the case for everything, and it's certainly not testing the one hundred most useful HTML5 features or anything like that.

More fundamentally, there are different degrees of "supporting a standard." Some demonstrations of the highly desirable and widely demanded CSS round borders helped explain this. The IE9 Platform Preview and WebKit both purport to support CSS3's rounded borders, and the Gecko engine (in Firefox) has an extension to provide rounded borders (the extension is nonstandard, but implemented in such a way as to not interfere with standard features). Rounded borders are something that developers are particularly keen on, since without CSS support, they have to be approximated with images, which is much less flexible (you can't easily change the colour or thickness of a border if it's done with images, for example). So in terms of desirability, they rank pretty high.

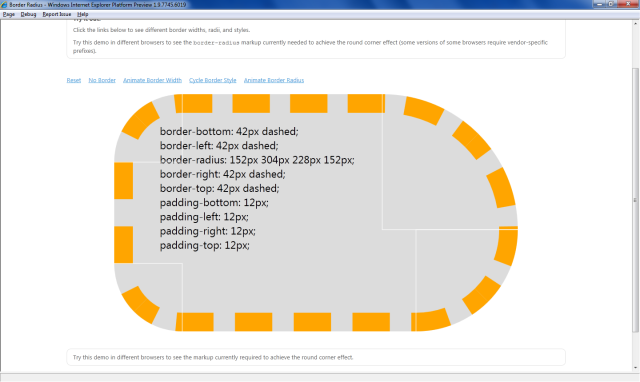

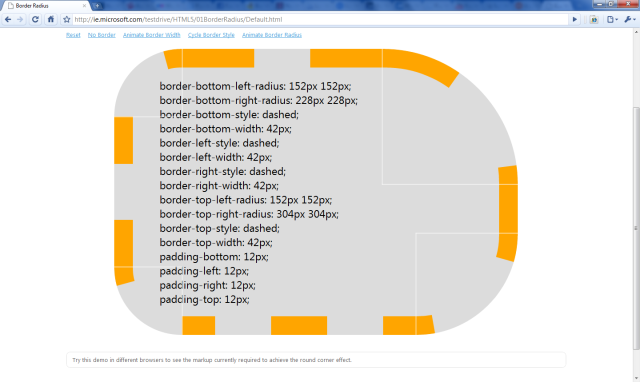

Unfortunately, they don't look consistent. At all:

These are two browsers that both support a feature. But they look completely different. This has two interpretations: either one or both of the browsers is wrong, or the specification is lousy (such that both browsers are doing what the specification says, even though it's surely not what any developer would want). In general, this kind of discrepancy isn't something that a test like Acid3 will reveal. It needs systematic, thorough suites of tests that verify each individual part of the specification, and ensure that the different parts of the specifications work together.

In developing these tests, sometimes errors in the specification will be revealed. But it's also likely that errors in implementations will be revealed, even implementations that are widely perceived to "support" feature X or Y. Acid3 can't show just how much of the HTML5 standards a browser supports. It can't even tell you very much about which parts of the standards aren't supported. To do these things requires much more thorough testing.

It's for this reason that Microsoft is continuing the work it did for Internet Explorer 8. With IE8, Microsoft developed, and delivered to W3C, a huge library of CSS 2.1 tests. Systematic testing was the only way to ensure that the browser truly lived up to the demands of the specifications. So for IE9, the company is developing a new raft of tests, the first batch of which have already been submitted to W3C. Microsoft doesn't want IE9 to have the same kind of test results as other browsers presently do; a feature isn't done until all the tests pass.

A case could be made that these other browsers are perceived as more compliant than they really are; while there are certain browsers that excel in certain areas (Opera's SVG support has long been extensive), other browsers also have considerable gaps. Sure, not as big as the gaps that IE8 presently has, but substantial nonetheless. All vendors clearly have plenty of work to do before the "same markup" goal really becomes reality.

Scoring well on the SunSpider JavaScript benchmark is similarly not an explicit target for IE9. SunSpider is useful, and tests JavaScript performance in many ways, but just as real web pages aren't written like the Acid3 test, real web applications aren't written like SunSpider. Real applications do things like optimize their design so that the basic page loads quickly, and then complex activities happen asynchronously in the background. SunSpider doesn't really test this style of development, and yet this is how real applications actually work.

This doesn't make SunSpider bad, but it explains why it's not a priority. It would be a mistake to optimize specifically for SunSpider, as SunSpider is not representative of real-world usage. Developers should optimize for reality, not for specific microbenchmarks.

Microsoft wants its HTML5 support to be stable and robust. This means that Internet Explorer 9 is unlikely to support every single part of the various specifications that make up HTML5; some parts are presently too much of a moving target to be viable. Other parts may be stable, but not relevant to the scenarios that the company is using to guide its development effort. But what the company will deliver will be thorough in a way that isn't necessarily the case with other browsers. Clearly the company has an up-hill struggle if its browser is to be perceived as highly conformant with Web standards. But it's certainly heading in the right direction.

reader comments

128