A campaign that forces sites running the Apache Web server to install highly malicious software on visitor's PCs has compromised more than 40,000 Web addresses in the past nine months, 15,000 of them in the month of May alone.

The figures, published Tuesday by researchers from antivirus provider Eset, are the latest indication that an attack on websites running the Internet's most popular Web server continues to build steam. Known as Darkleech, the rogue Apache module gets installed on compromised servers and turns legitimate websites into online mine fields that expose unsuspecting visitors to a host of dangerous exploits. More than 40,000 domains and website IPs have been commandeered since October, 15,000 of which were active at the same time in May, 2013 alone. In just the last week, Eset has detected at least 270 different websites exposing users to attacks.

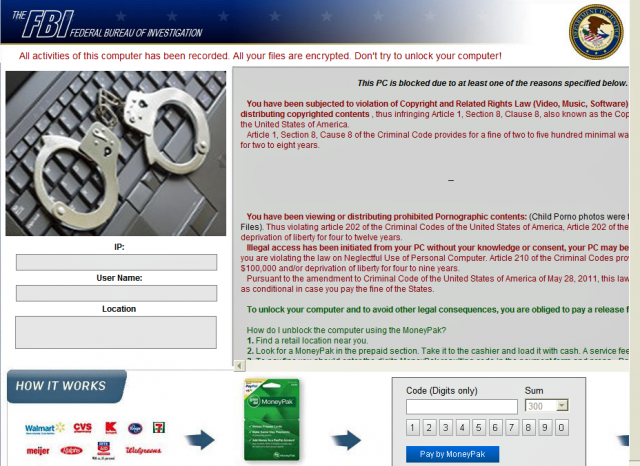

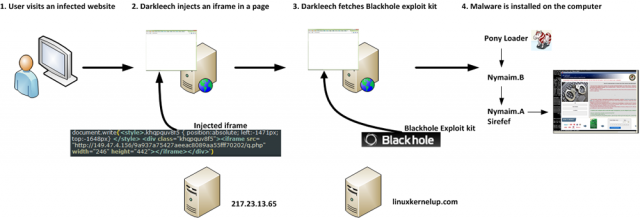

Sites that come under the spell of Darkleech redirect certain visitors to malicious websites that host attack code spawned by the notorious Blackhole exploit kit. The fee-based package available in underground forums makes it easy for novices to exploit vulnerabilities in browsers and browser plug-ins. Web visitors who haven't installed updates patching those flaws get silently infected with a variety of dangerous malware titles. Among the malware that Darkleech pushes is a "Nymaim" piece of ransomware that demands a $300 payment to unlock encrypted files from a victim's machine. Other malware titles that get installed include Pony Loader and Sirefef.

"This campaign has been going on for a very long time," Eset malware researcher Sébastien Duquette wrote in Tuesday's blog post. "Our data shows that the Blackhole instance has been active for more than two years, since at least February 2011."

Eset's research is consistent with April coverage from Ars reporting that an estimated 20,000 Apache websites were infected by Darkleech in just a few weeks' time. Sites operated by The Los Angeles Times, Seagate, and other reputable companies were among the casualties. Like Ars, Eset found the Web malware employs a detailed array of conditions to determine when to inject malicious links into the pages shown to end users. Among other things, Eset wrote that users will only be attacked when their browser reports they're using Microsoft's Internet Explorer browser or Oracle's Java plugin. Eset's findings are also consistent with recent figures from Google showing that the vast majority of malware attacks are spawned from legitimate sites that have been hacked.

The chosen few

Darkleech has also been known to pass over visitors using IP addresses belonging to security and hosting firms, people who have recently been attacked, and those who don't access the hacked pages from specific search queries. By being highly selective in targeting potential victims, Darkleech developers make it harder for security defenders to unravel the campaign and block infections. Visitors who are selected are served an HTML-based iframe tag in a Web page from the legitimate site that has been compromised. The iframe exploits code from a malicious site under the control of attackers.

Darkleech, which also goes by the name Linux/Charpoy, is able to tailor exploits to the geographic region of the infected victim as well. Ransomware that infects US-based visitors, for instance, purports to come from the FBI, while ransomware hitting people in other countries is adapted accordingly.

In October, Darkleech underwent a makeover that changed the format of the URL in the malicious iframe so it's harder to detect. It works by decrypting four different text strings and then calculating a cryptographic hash to determine if a visitor should be served an iframe. The randomly generated link that leads to the attack site is extremely hard to detect as malicious except for its telltale ending "q.php."

As has been the case with previous investigations, researchers still don't know how the Darkleech module takes initial hold of the sites it infects. Speculation has surfaced that the servers are compromised by exploiting undocumented vulnerabilities in the CPanel or Plesk tools administrators used to remotely manage sites, but there's no hard evidence to back up that theory. Researchers also reckon sites may be taken over by cracking administrative passwords or by exploiting security flaws in Linux, Apache, or another piece of commonly used software. Darkleech in part uses CPanel and Plesk servers to handle certain aspects of the iframe injection and payload delivery, but other parts rely on the Apache server itself, Pierre-Marc Bureau, Eset's security intelligence program manager, told Ars.

Because there are usually many websites hosted on a single server, there's often multiple domain names pointing to a single IP address, so Eset researchers are unable to determine just how many Apache-powered websites are infected by Darkleech. The total is "probably lower" than the 40,000 estimate, Bureau said.

The Eset report comes two weeks after researchers from security firm Sucuri unearthed a new malicious module infecting Apache servers. They're still not sure if the plug-in is a newer, stealthier version of Darkleech or a completely different tool developed by a rival crime group. Researchers in recent months have uncovered a third piece of malware that causes websites to expose visitors to attacks. Known as Linux/Cdorked, it targets sites running the Apache, nginx, and Lighttpd Web servers and, as of May, had exposed almost 100,000 end-users running Eset software alone to attack.

Only you can prevent Web server hacks

With so many threats successfully targeting mainstream Web servers, administrators should take care to lock down their systems by following good security hygiene. One step is to ensure all default passwords have been changed to a one that's long and randomly generated. Also key is to make sure all software components—including the operating system and all applications—are fully up to date. It's also not a bad idea to use a website security scanner from time to time and to occasionally check the cryptographic hash of the HTTP daemon of the Web server to make sure it hasn't been tampered with.

reader comments

47