Nathan Oostendorp thought he’d chosen a good name for his new startup: “Ingenuitas,” derived from Latin meaning “freely born” — appropriate, he thought, for a company that would be built on his own commitment to open-source software.

But Oostendorp, earlier a co-founder of Slashdot, was aiming to bring modern computer vision systems to heavy industry, where the Latinate name didn’t resonate. At his second meeting with a salty former auto executive who would become an advisor, Oostendorp says, “I told him we were going to call the company Ingenuitas, and he immediately said, ‘bronchitis, gingivitis, inginitis. Your company is a disease.'”

And so Sight Machine got its name — one so natural to Michigan’s manufacturers that, says CEO and co-founder Jon Sobel, visitors often say “I spent the afternoon down at Sight” in the same way they might say “down at Anderson” to refer to a tool-and-die shop called Anderson Machine.

Sight Machine is adapting the tools and formulations of the software industry to the much more conservative manufacturing sector. Changing its name was the first of several steps the company took to find cultural alignment with its clients — the demanding engineers who run giant factories that produce things like automotive bolts.

At its heart is something of a crossover group — programmers and designers who are comfortable with Silicon Valley-style fast innovation, but who have deep roots in Midwestern industry. Sight Machine’s founders quickly realized that they needed to sell their software as a simple, effective, and modular solution and downplay the stack of open-source and proprietary software, developed by young programmers working late hours, that might make tech observers take notice.

Sight Machine staff in the Ann Arbor warehouse where they built a full-scale mockup of an auto-plant quality-control station to test their system

“Nate saw these big bottlenecks in the way things were being done” in industrial computer vision, says Sobel. “There were no high-level frameworks like Ruby on Rails, and everything is set up to be pass-fail; there are no higher-level analytics.” Sight Machine set out to build what they hope will become “Rails for vision.”

Sight Machine’s co-founders built much of SimpleCV, an open-source computer vision library that’s designed to be accessible to people who aren’t experts in the field. (O’Reilly has published a book on SimpleCV, written by four of Sight Machine’s principals.)

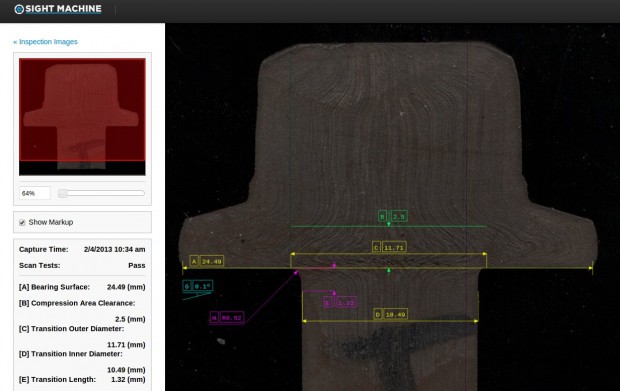

Sight Machine’s software measures grain-flow characteristics in a fastener, using little more than a commercial flat-bed scanner.

Anthony Oliver, the company’s CTO and co-founder, worked on automation at a big car plant in Toledo, Ohio, before being laid off during the recession and deciding to switch tracks. “They had 200 cameras at the plant, but they were treating them like black boxes — after the picture was done, they’d throw it out. They weren’t collecting trending patterns, doing self-correction,” he says. The plant had bought computer vision systems from integrators that weren’t making much data available for higher-level analytics.

“There’s a huge disconnect [in heavy industry] from the Internet way of doing things,” says co-founder Kurt DeMaagd, also a Slashdot co-founder. “Process engineers are very data-driven, but they haven’t tried these new tools, and they’re not working in real-time.” Oliver says the goal was to build a system that would raise immediate flags, “as opposed to saying, ‘hey, a week ago we were having quality-control problems.'”

Their system puts a clear emphasis on the value of software rather than hardware (though a few of the industrial-quality components, in particular the CCD cameras they use, remain expensive). It can stand on its own as a module in an automated factory; no system integrator necessary. And, in the modern form, it emphasizes data retention and high-level analytics.

Sight Machine’s first client manufactures bolts — fasteners, as they’re called by industrial insiders — checking the integrity of their steel at the beginning and end of each batch by slicing one open and scanning it on a cheap flatbed scanner. Software discerns the dimensions of the steel’s grain (compression lines that form when the head of the bolt is pounded out) and provides an instantaneous quantitative measure of quality. The previous method had involved employees looking at bolts through microscopes.

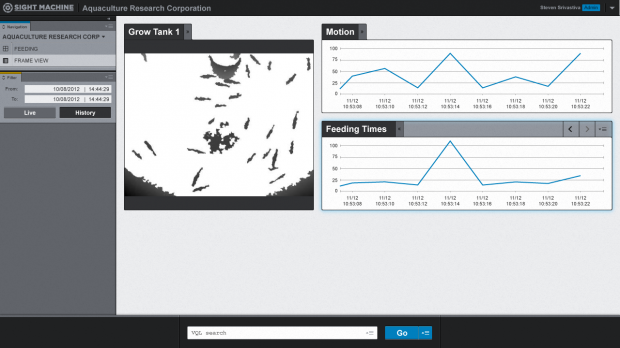

Swarming in a tank at a fish farm. Sight Machine’s object: to signal the feeding system to stop putting food in the tank once the fish had eaten enough to be satisfied. Photo: courtesy Sight Machine.

Another client, a fish farm in Michigan, uses Sight Machine’s software to manage feeding — determining when the fish have had their fill by measuring changes in movement and switching off the farm’s auto feeders. Another proposal for an Ann Arbor-based deli and mail-order house would use Sight Machine software to watch for bunch-ups in the production line and tell managers to send help to, say, the jam-labeling station if the employee there is having trouble filling orders fast enough.

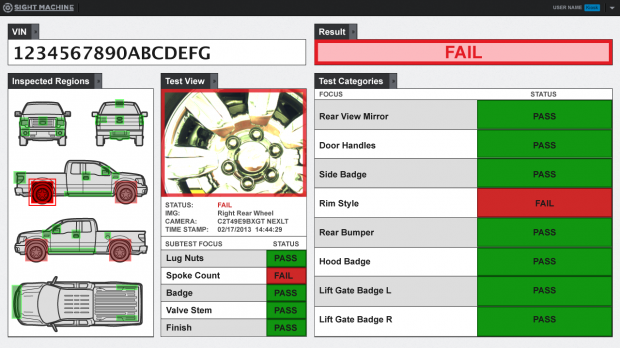

And in a live demonstration that I saw at the company’s industrial-park development space, Sight Machine software detected a misapplied badge on the back of an SUV. That’s a problem that could be corrected quickly and easily at an automaker’s quality-control checkpoint, but if a car that doesn’t have four-wheel drive makes it to a dealer’s lot with a chrome “4×4” badge glued to the tailgate, the logistics and inventory costs of fixing the problem will be substantial.

Cameras photograph a car as it rolls through an inspection station, and signal in real-time whether trim features like badges, taillights, and rims are correct. Photo: Jon Bruner.

In addition to a real-time check like this one, Sight Machine’s software can also aggregate results for higher-level analysis. Engineers can, for instance, call up photos of every yellow car with a bent antenna.

Photo: courtesy Sight Machine.

Industrial firms tend to be conservative in adopting new systems, for a reason: the costs of a plant outage are huge (consider that a large auto assembly plant might produce more than 60 vehicles per hour — an outage of just one minute is equivalent to one car’s worth of lost production). They also tend to have enormous amounts of capital tied up in big, integrated production systems, making changes costly.

Sight Machine’s founders have approached both of those obstacles carefully. The company’s developers work in an industrial park in Ann Arbor, Mich., where they built a mockup of an auto-plant inspection station to test their software under factory conditions. Several of them have worked in heavy manufacturing, including automotive and defense, and the company has its roots at the decidedly machine-oriented Maker Works, a maker space across the street that offers Michigan’s industrial prototypers access to plasma cutters and CNC mills.

Early prototypes got some upgrades to meet the expectations of plant managers used to heavy-duty equipment. Sight Machine’s system uses costly CCD cameras instead of cheaper consumer-grade cameras. Design director Kyle Lawson says, to make the company’s first camera mount he “took a Logitech webcam stand, broke it down, and filled it with pennies to make it feel industrial.” (Now he fabricates heavy-duty camera mounts himself at Maker Works.)

As for the problem of weaving a new assembly line component into an old plant, Sight Machine’s software is free-standing and can be provided as a service or licensed to run locally — minimal integration with plant controls needed. That’s an important consideration for a cautious assembly-line manager who’s experimenting with a startup’s software.

Software and industry are inching closer; the industrial Internet will make it easier for innovators to turn physical-world problems into software problems, and then solve them using rich open-source tools and pervasive networks. Along the way, I think we’ll see lots of stories like Sight Machine’s.

This is a post in our industrial Internet series, an ongoing exploration of big machines and big data. The series is produced as part of a collaboration between O’Reilly and GE.