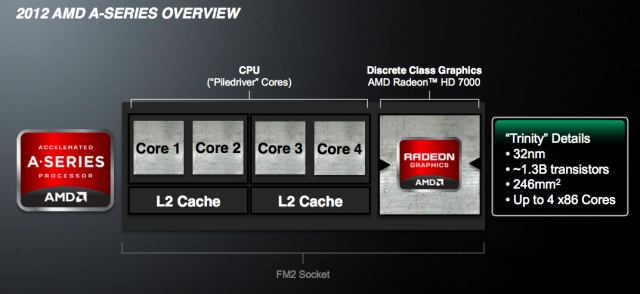

Today, AMD is announcing availability for a few new A-series desktop processors. Versions of these chips, codenamed Trinity and based on AMD's Piledriver architecture, have already been shipping in laptops and desktops for some time now, but this marks the first time that the chips will be available to consumers and system builders directly.

The chips aren't bad—the integrated graphics processor on some of the chips are capable of beating Intel's HD 4000 GPU in gaming performance, though the CPUs aren't quite capable of beating last year's Sandy Bridge processors at similar clock speeds. For AMD, the issue is that they're still talking mostly about desktop and laptop chips.

AMD is being shut out of new markets

That's not to say that Intel has moved away from desktop and laptop processors—the PC industry may not be growing much these days, but it's still sizable and profitable for the people making the chips (if not always the people who make the computers themselves). Intel continues to roll out new Ivy Bridge processors for mid- and low-end desktops and laptops, and desktops, laptops, and Ultrabooks factored heavily into its presentations about its upcoming Haswell architecture at IDF this year.

There's one thing in the Haswell presentation that is conspicuously absent from AMD's latest Steamroller architecture update: tablets. With Haswell, Intel is pushing the power consumption of its flagship x86 CPUs lower than ever before with a 10W processor aimed at Ultrabooks and tablets. Going even lower on the power consumption scale, its upcoming Clover Trail Atoms (and, going beyond that, next year's Bay Trail chips) are going to end up in lower-cost tablets and even smartphones. It has taken Intel a few years to develop serious, competitive chips to combat the ARM-based offerings prevalent in tablets and smartphones today, but by this time next year I expect Intel to be available in many more mobile devices than it is presently.

AMD has produced a lower-power processor based on the the Bobcat architecture found in AMD-based netbooks and budget laptops—codenamed Desna, the AMD Z-01 has found its way into very few tablets to date, with last year's MSI WindPad 110W being one of the only examples. A follow-up, codenamed Hondo, is apparently in the works—the latest information on the chip is that it's a 40nm part with a 4.5W TDP, and that its graphics performance should be superior to Clover Trail's—but details on are very difficult to come by. Hondo could, theoretically, give AMD some presence in the tablet market, but Atom tablets have so far been much more numerous and it still leaves the company without a higher-performing Haswell competitor or a more power-efficient version for use in smartphones.

AMD did recently rehire Jim Keller, who was lead architect on the K8 architecture that saw AMD through its early-2000s heyday before moving onto PA Semi and working on Apple's A4 and A5 chips. This may speak to a desire to prioritize chips for small, low-power devices, but even if so it could be years before we see Keller's hire make a difference: chips take a long time to design and manufacture, and the AMD of the last few years has shown a frustrating tendency to miss the deadlines it sets for itself. If there are new tablet and smartphone-oriented chips coming from AMD, we aren't going to see them soon.

AMD is losing ground in its traditional markets

So far, AMD hasn't seen much success in the tablet market, and it hasn't shown up to the smartphone fight. What's even more worrisome is that their relevance to anything but low-cost PCs is also melting away bit by bit. This has been happening slowly but steadily since 2006: First, Intel's Core 2 processors beat AMD's then-current Athlon X2 processors in clock-for-clock performance, but an aggressive price war kept AMD competitive in the mainstream market.

As quad-core processors became more common, it later became the case that a cheaper quad-core processor from AMD could beat a dual-core processor from Intel in heavily-threaded workloads, but AMD's dual-core processors were confined to the low end of the market, and the introduction of Turbo Boost, Hyperthreading, and ever-better performance-per-watt eventually helped Intel overcome this in the Sandy Bridge and Ivy Bridge epoch.

Finally, AMD had its integrated graphics performance to fall back on. Its argument in recent years has been that its chips offer more "balanced" performance than Intel's—a "good enough" CPU paired with an integrated graphics part that could replace low-end previous-generation dedicated graphics chips. This argument is still largely true in AMD's current Trinity products, but even this argument is slowly losing its potency as Intel's integrated graphics solutions catch up by leaps and bounds; even two years ago, Intel's graphics were basically unusable for gaming, but current chips provide a reasonable level of performance for older games or newer titles with settings turned down.

The trouble with AMD is that it doesn't have big plans to chase new growth markets like tablets and smartphones, and it's running out of niches to occupy in its traditional desktop and laptop PC markets. The PC market needs AMD (or a company like it) to keep Intel on its toes and to keep prices down, but the company's fumbles and inability to execute have made it hard to have a lot of faith in it. In both the PC and server markets, AMD offers a decent alternative to Intel for the price-conscious, but it looks increasingly unlikely that they'll ever again be anything else.

reader comments

153